Recent news from Okinawa is good for all those concerned with seeing US military bases out of Asia, although, naturally, it would be foolish to imagine that peace is in sight for the residents anytime soon. This has been a long struggle and will continue for some time yet: Clinton and Obama have put the pressure on Hatoyama (who’s bound to be feeling it from his own ranks and is, besides, hardly an anti-establishment figure). The pro-US and pro-military voices from the Koizumi era (subject of Gavan McCormack’s precise dissections) haven’t gone away, and won’t: see, as an example of how calls to revise the Constitution aren’t the exclusive preserve of the Japanese right, this typically elegant but vapid puff-piece in praise of the US alliance from The Economist.

The people of Okinawa have suffered so much, and for so long now, all the while with the democratic process itself getting insulted and distorted: elect an anti-base mayor and, if past history’s anything to go by, chances are they’ll either get leaned on or ignored by Tokyo. Meanwhile the crimes keep happening, the environment keeps getting harmed, the eye-sore stays somewhere.

This is all the time a global problem, and a problem which requires a global perspective, and that aspect - its interconnection with other struggles in Asia and around the world, their potential impact on US policy elsewhere - is too often forgotten. This is also - for some of my habits at any rate - a representational problem of a quite peculiar kind. The problem, for those of us acting in solidarity with the campaigns in Okinawa and elsewhere through Asia, comes not from a paucity of representation but rather from its surplus: all that documented horror can paralyse, and all those examples of heroism and determination disable. We’ll never live up to those examples, so the old question returns: what is to be done?

It’s been in the spirit of trying to re-think this struggle globally these last few days that my mind’s gone back to images from Joon-ho Bong’s masterpiece The Host (괴물, 2006). Eschewing an allegorical treatment, Bong’s ‘host’ monster’s relationship to US imperialism and presence on the Korean peninsula is – unless you miss the first ten minutes of the film - made as clear as can be. There’s no getting away from the fact that what you’re watching is a direct assault on the US vision for the region. The Host has plenty of CG trickery and plays by the best rules of the horror genre, but its anti-imperialist theme was heard too: it drew a record audience of ten million people on release in the Republic of Korea.

That monster imagery - vital and accurate for the film, for Korea and for Okinawa - isn’t what I’ve been reflecting on this week, though. Bong’s representational triumph, in helping develop our understanding of and resistance to the US occupation of Asia, is his development of a kind of slob realism. Partly this is to do with getting a proper sense of the monster’s dimensions: Bong’s vision is expertly realised, but his aesthetic is a shabby one, its dominant colours brownish, sometimes like brackish water. This is a monster to be feared and loathed, not one to be secretly admired or given over to subconscious projections and investments.

A slob aesthetic offers political ways out of the representational dilemma too. The dilemma, it seems to me, when representing the monstrous US presence is that most artists have to choose between two equally undesirable emphases. Stress the power and horrors of the monster and we’re all left feeling as weak and vulnerable as we were before we encountered the representation. Stress the exceptional heroism and bravery of those resisting the monster (a bravery, I do want to stress, with ample historical examples to draw on), and we’re left with the full realisation of our own - and our historical moment’s - inadequacy and isolation.

Slob realism suggests the chance of a third way, and offers us one way of imagining agency without automatically excluding ourselves. Park, hero of the The Host, is an exaggerated version of normality. This isn’t Lukacsian typicality, either: he’s a bit of a loser, beset by family problems, out of shape, run-down. That he ends up helping bring down the monster - and that the whole fight keeps pace with a series of domestic sub-plots and dramas - restores a sense of perspective the other kinds of disaster-film or fantasy reconstruction often miss or distort.

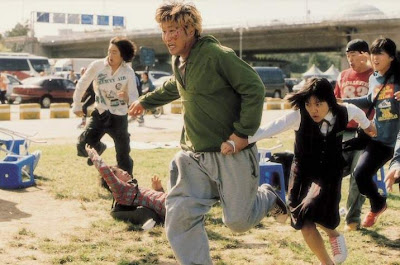

One scene in particular stays with me: there’s a moment when Park is running from danger, and realising others in his family are in immediate danger. All of a sudden everything’s in slow motion and, without losing a real sense of risk and potential devastating loss, we’re made aware of the ridiculousness of it all, the films being referenced, the generic horror moment being hammed up. Our situation, those images suggested to me on first viewing, is desperate, not hopeless. The slobs (us, ordinary people, the guy on the screen), are going to keep bumbling through, fighting back. This was a scene from a struggle - fought by ordinary, weak, vulnerable but brave people - not a substitute fantasy of rescue by a super-hero saviour.

It was also, of course, a moment of physical comedy at the same time as it was the clearest statement there can be: there’s a monster occupying us, polluting our river, spreading disease and danger. Something has to be done. It’s not, as the cliché goes, that if you didn’t laugh you’d cry, but rather than you’re going to have to laugh and cry.

Thinking about the campaigns to come, it’s an image I’m glad to have still with me in memory.

FOOTNOTE

Linda Hoaglund has made a very different kind of movie - a documentary, and a recovery of historical memory - dedicated to rediscovering the art and creativity of an earlier period of Japanese activism. It’s important; especially given the anniversary of the Treaty struggle this year, and the parallels we should all be drawing with our current situation. You can see a trailer for it here.